THE

WOMANLY ART

AN

OVERVIEW OF WOMEN'S BARE KNUCKLE BOXING

ANDREW

SALMON

Elizabeth Stokes, Anna Lewis, Hattie Stewart, Alice Leary, Hattie Leslie, Hessie Donahue, Cecil Richards, Dolly Adams, Polly Burns – if these names are unfamiliar to you, then keep reading.

The women listed above were just a few of the many great women pugilists of the Victorian age. Not much is known about these accomplished fighters because the press at the time rarely covered their matches unless to either ridicule them or call for their abolishment. Society, for the most part, looked down on female fighters in that bygone age (some would maintain people still do) and, as a result, the matches were rarely advertised. It is only recently that their rich history is gradually being stitched together. The Bare Knuckle Boxing Hall of Fame just inducted its first batch of female fighters this past July.

Women fighters have been around since ancient times, but for the sake of this overview we'll limit our focus to the dawn of female prize fighting. The Hall of Fame's coordinator, Scott Burt, tells us it all began with Elizabeth Stokes. As the winner of the first ever recorded female bare knuckle boxing fight in 1722, Stokes fought Hannah Hyfield for a prize of three guineas. The women fought with a half a crown in one fist. The first to drop the money, lost the fight. This set a precedent for future fights. This was a smart addition to the women's Fancy, as the closed fist cut down on scratching and gouging.

Much like its male counterpart, women's bare knuckle boxing began with very different rules. The womanly art allowed hair pulling, kicking, kneeing, scratching and gouging to all parts of the body. Wrestling throws were also legal, making the sport more a primitive form of mixed martial arts than simply boxing. As such, it displayed a marked similarity to the Boxe Francaise or Savate fighting, which combined boxing with a variety of kicks using both heel and toe.

The fights were brutal and savage affairs. As a result, the women were often severely injured, and some died in the ring. Usually trained by men, either their husbands or fellow pugilists, the women fought men as well as each other, sometimes winning despite the tremendous risks. There were exceptions, such as the time Hessie Donahue knocked out John L. Sullivan during an exhibition bout when Sullivan angered her by accidently hitting her too hard.

The women often boxed bare chested. This served two functions. The first served the promoters with the obvious salacious draw of sweaty, topless women punching away at each other, but there was a sound reason for this as well. Without antibiotics of any kind, the risk of infection ran high. Dirty fabric pressed into open cuts incurred during a fight could mean death for a fighter. And injuries did not just result from a fist or boot heel. There was the very real risk of the various wires found in female clothing of the time puncturing the skin as well.

Women's bare knuckle boxing became popular on both sides of the Atlantic as the eighteenth century drew to a close despite being considered indecent and unladylike by many. Women's boxing classes were held in gymnasiums everywhere, but catered mostly to the upper class.

As the sport was open to all comers and substantial prizes were to be had. This prize money far exceeded what the lower or middle class women could earn at other jobs. As a result, despite the risk, the temptation to toe the line was, for many, the only avenue out of poverty. For others, it was an opportunity to escape the confines society placed on them, to be strong, independent and capable.

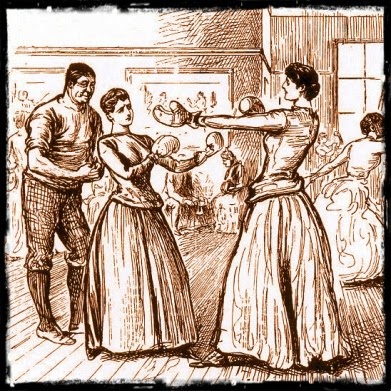

By the 1880s, women's boxing flourished in dance halls and at fairgrounds where women put on boxing displays and/or sparring with fair goers and engaged in tag–team fights where male and female teams (often husband and wife) squared off against each other with a tag to switch partners. As the 19th century drew to a close, the sport, still frowned upon by the press, gained more respectability. Bare knuckles eventually gave way to gloves as the Queensberry Rules were put in place.

The sport continued into the 20th century and was even an exhibition sport at the St. Louis World's Fair/Olympics in 1904. It was also considered an excellent way for a young lady to stay healthy and safe well into the 1950s, though by then, the sport had lost most of its ferocity. By the 1970s, women boxers began to fight in greater earnest to secure the rights and opportunities their male counterparts enjoyed.

If you want to delve deeper into the world of female bare knuckle boxing, check out the Hall's website above or pop over to this Russian site, Female Single Combat Club, which offers both English and Russian versions of its pages. Here they explore the history in depth and I'm indebted to them for the research materials I found at the site.

No comments:

Post a Comment